Employers, colleges and families may not agree on much, but they tend to agree about this: our K-12 students need to develop essential skills like self-direction, collaboration, communication and creativity to successfully navigate college, career and community life. Trouble is, standardized tests and traditional assessments do not adequately capture whether students have developed these deeper learning skills. Too often, we test things we may not value and may not be all that important. Fortunately, leaders are working to change this, and the results are promising.

The state of New Hampshire has sought to move beyond assessments of content knowledge by capturing students’ level of proficiency in important 21st century skills such as self-direction with the goal of scaling these innovations across the state. To accomplish this, leaders formed a unique research-practice partnership between JFF, New Hampshire Learning Initiative, the New Hampshire Department of Education and the Center for Innovation in Education.

Their efforts to implement, scale and study the effects of deeper learning assessments across the state provide a host of insights for educators, leaders and policymakers who are interested in the best ways to prepare youth for 21st-century life.

The partners sought to combine a developmentally backed research framework, rich teacher professional development and new instructional strategies in the classroom. They then leveraged a pre-existing statewide performance assessment system rooted in competency-based education (PACE) to implement deeper learning practices—what they call “work study practices” (WSPs)—across the state. To track how that implementation spread and its impact, they designed a multi-year study that involved educators, leaders and students from across New Hampshire. Below is a summary of that study and what it discovered.

- What is the extent to which integrating a set of deeper learning practices improves outcomes on field-leading academic performance assessments?

- Do outcomes improve particularly for marginalized groups and students furthest from opportunities?

- Does a collaborative, learner-centered diffusion approach accelerate uptake and scaling of evidence-based practices?

- Improving Learning: The crux of their work focused on teachers who opted-in to professional development to learn how to build performance tasks that embed instruction in self-direction.

- Partnering with Research: Education leaders worked to translate the Essential Skills and Dispositions framework to guide the development of assessment rubrics and tools. To bridge research and practice, educators:

- Researched the framework, then applied the learning progressions it contains to name the specific work study practices to be prioritized and how they would be supported and assessed

- Designed activities for work study practices that would be embedded in the PACE system

- Created instructional and coaching materials that are developmentally appropriate and aligned with the learning progression for the self-direction WSP

- Taking to Scale: Explore the blog series that details how this research-practice partnership distributed ownership, spread practices across the state and created multiple entry points to address different system needs and ensure greater sustainability.

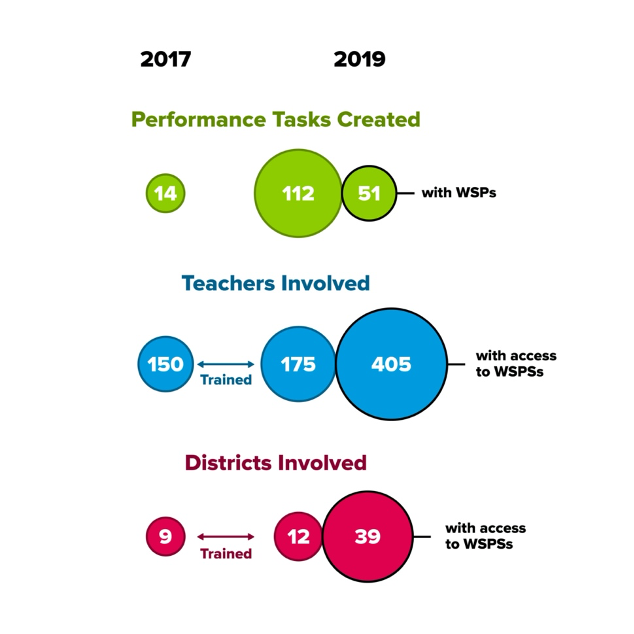

The following graph illustrates the growth over three years in the numbers of performance tasks created, teachers involved and districts included.

Four pilot school districts participated in the formal research study. During the 2018-2019 school year, the following data was collected:

- 1680 student records with information on teachers, grade level, class content area, performance assessment proficiency score on academic content, self-direction proficiency score and key demographics.

- 117 teacher engagement survey responses exploring the motivations and range of student-centered learning, deeper learning and competency-based instructional efforts they used.

- Three focus groups with mixed grade students in three of the four study districts.

- Participant observation and collection of field artifacts related to professional learning in work study practice performance task development and iterative design cycles for the creation of rubrics and tools for assessment.

- After the first year of the intervention, data collection revealed a major weakness in the study design. Competency scoring on self-direction had not been validated and educators were using a range of systems and methods to score the work study practice of self-direction. It was apples, oranges, bananas and pineapples and we couldn’t compare one with the next with any sense of rigor. So, members took a step back and re-oriented the study to focus on validation of the self-direction rubrics and evidence collection tools. This course correction made all the difference!

- In an analysis of 251 11th grade student records, the work study practice of self-direction and PACE academic content scores across subject areas showed that those who have higher work study practice self-direction scores also tended to have higher PACE content scores. Though this is a strong degree of correlation at a statistically significant level which does suggest a relationship, it is not a causal link and the direction of influence is not known.

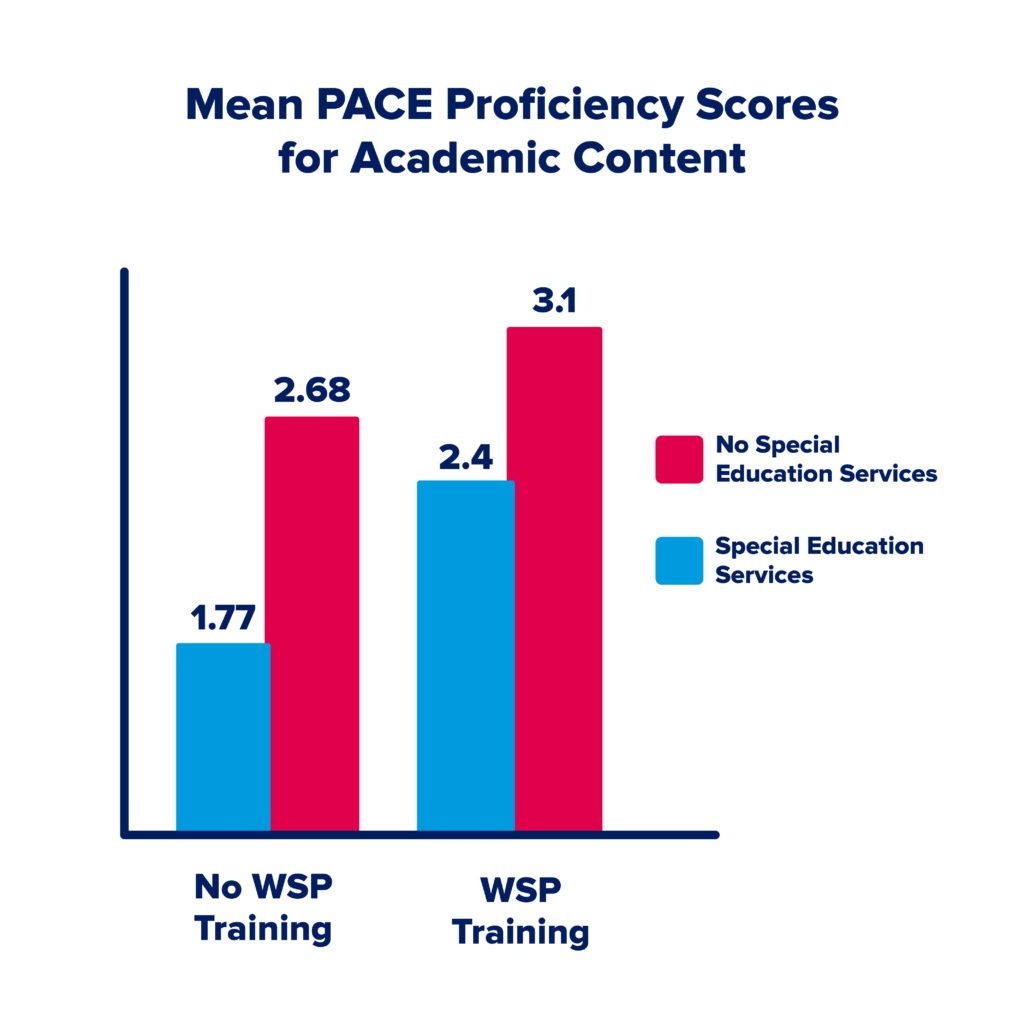

- Students who had a teacher with specific training in embedding and assessing work study practices performed higher in academic domain knowledge than students who were not taught by a teacher with work study practice professional learning. It’s unclear whether it was the training that produced this effect or something like the teacher’s already existing inclination to pursue rich professional learning and its application, but the absence of a negative relationship was still encouraging.

- Evidence that suggested that the more training and professional learning a teacher had in work study practices the greater the academic outcome for students. As above, these findings should be interpreted as exploratory or descriptive rather than explanatory.

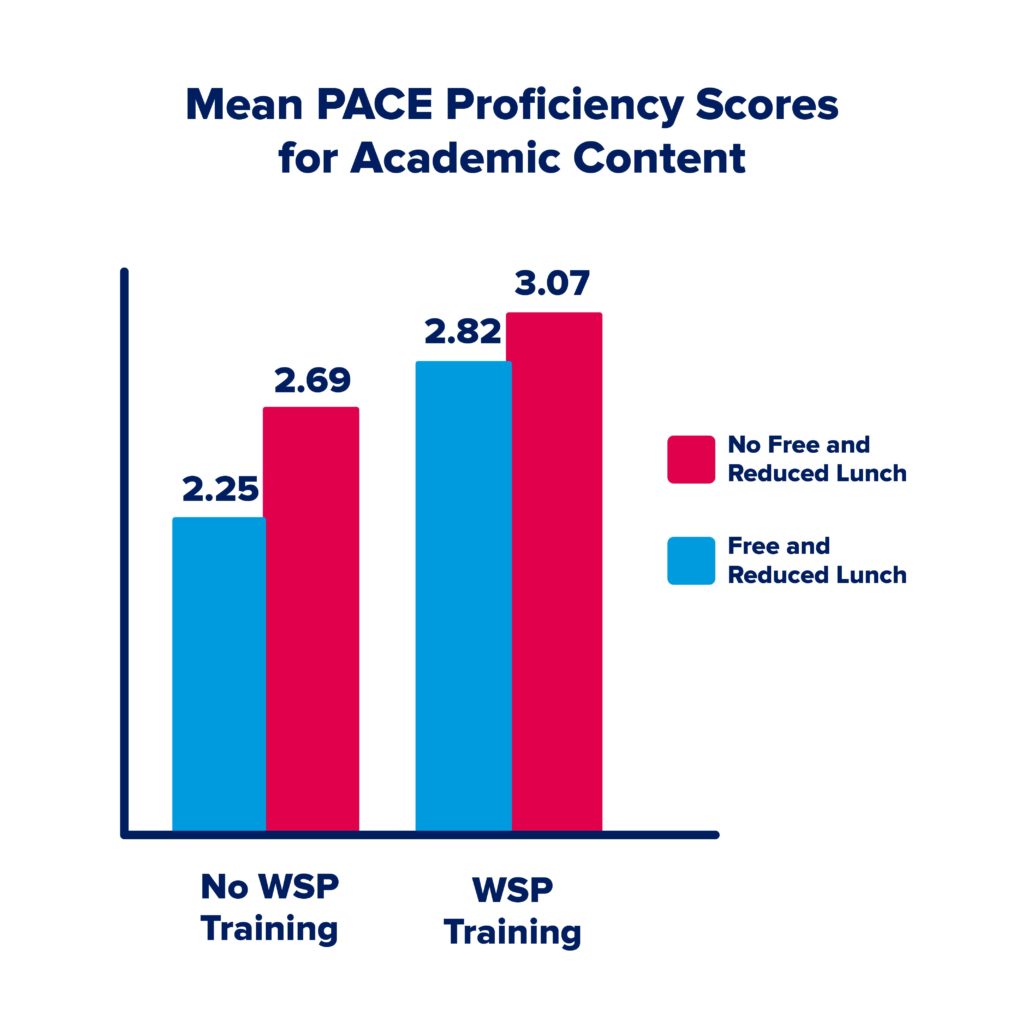

- There were larger gaps in both mean proficiency scores on self-direction as well as PACE academic content knowledge for students receiving special education services as well as those receiving free or reduced lunch, suggesting that additional time and resources may be needed to personalize and support the development of work study practice skills among these students.

The following graph depicts both the growth and the gaps that remain.

Educators

- Instruction and formative assessment of work study practices should be embedded as a distinct activity separate from academic content instruction and assessment.

- Participation in professional learning related to quality performance assessment and work study practice instruction is linked to increased academic achievement for students.

- Personalized instruction is needed to ensure that students furthest from opportunities receive the necessary supports to become proficient in these essential skills.

System leaders

Diffusion and scaling were supported by:

- A statewide intermediary dedicated to increasing the capacity for districts and teachers to create personalized, student-centered instruction

- A process that used internet-based technology to allow teachers to engage in performance task development across geographic and time boundaries

- Active engagement of teacher leaders who built capacity in their districts and lent credibility to the process by piloting and co-creating key assessment instruments

Policymakers

- The study provides evidence of what a state or consortium of districts may do to spread promising practices and enlist greater buy-in for specific reforms. If there is a statewide intermediary dedicated to increasing the capacity for districts and teachers, teachers will be more likely to create personalized and student-centered instruction.

- Separate from student outcomes, the work study practices are diffusing and scaling strongly in New Hampshire by being implemented within the state’s existing alternative accountability system (PACE).

Funding for this project is provided by the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation.

Photo courtesy of JFF.