I am so tired of being confused.

All those years of knowledge,

and still I lose.

Is it C or B? Should I choose

A or D?

I second guess myself; which

letter will it be?

Work your way up the worn linoleum floors of Southwest High School, twisting through packs of students until you reach the third floor. Swing open the heavy door to a science lab. Even though the room features sinks and eye-wash stations, the students in this classroom aren’t doing normal science experiments. The dozen or so students – all of whom are students of color and most are immigrants from Mexico, Central America, the Congo, the Caribbean – are regional student leaders doing the work of developing policy to make their school more equitable.

This isn’t typical student council stuff. They don’t plan dances. They don’t choose the theme and activities of spirit week. Instead, these students work as activists in the school: identifying problems, researching their root causes and impact and developing policy solutions.

This year, their work is especially personal. A chain reaction of data, labels, and media attention has targeted the school. The school’s low test scores earned it a “priority improvement” rating. That means the state will have to get involved and “fix” the school, which may mean replacing its comprehensive programming with a narrower focus on career and college.

The students, however, aren’t buying the narrative. As members of Southwest’s Student Board of Education, a district-supported school club aimed at increasing student voice and leadership, the students are tasked with shedding light on these inequities and pushing back on them. They readily concede that the school’s test scores need improvement. But, the students say, look at our student population: 91 percent are Latinx, many of whom are emergent-bilingual, and 92 percent qualify for free or reduced lunch, which is high even for this diverse district. The flagship public high school, for example, has 54 percent students of color and 34 percent qualifying for free or reduced lunch. The students notice the stark contrast when comparing these numbers to other nearby schools, and they ask, “Why would they segregate us like that?” Digging deeper, students then explore opportunity data. They discover that only twenty of 1,400 students had access to AP Calculus. “Rich people have secrets that helped them get rich,” one student says. “The secrets start here in school. What do those 20 students in calculus know that we don’t? Why can’t we have access, too?”

The system, they say, is inequitably designed. The classroom, school, and district-wide approaches, the school rating system, its reliance on test scores, and leaders’ interpretations of the causes of failure — they aren’t designed to serve all youths’ needs. They’re designed to preserve advantage.

This pressure I feel will trample me

like gravity.

They say don’t flip through,

just move.

Your destination will get you

to 52.

The stanzas above are written by a younger member of the Southwest SBOE team. The team plans to use her poem as their hook in a youth policy competition sponsored by their district later this year. They see the testimonial aspect as naturally drawing the reader into the problem and into their school, exposing the pressures of standardized testing, their reductive nature, and what it does to learners’ sense of themselves and their futures. To them, being seen as more than faceless test-takers is an important first step.

Students in the SBOE have been struggling to build nuanced arguments since the fall and have landed on the need to alleviate the pressure of naming and shaming students through test scores. They feel they are caught in the school-to-prison pipeline, a cycle of disempowering and disciplining youth during their school years that sets many up for future failure and exposure to the carceral state.

The SAT exam is especially nefarious in the students’ eyes, not only as an unwelcome yearly test but as a symbol of race and class-based inequality. They see other area high schools with more balanced race and poverty demographics scoring far higher than Southwest High students. They see White, affluent peers hiring tutors to help boost their scores. Most of the Southwest students say they can’t afford to retake the test in the first place, let alone hire outside help.

The biggest travesty, the students say, targets Southwest High’s large emergent-bilingual population. The SBOE club, much like the school itself, features a diverse range of linguistic knowledge. Some students speak mostly in Spanish and others mostly in English. Bilingual speakers translate for their peers.

On the SAT, though, only knowledge shown in English counts. Contributions that are essential to the team’s function in its science lab classroom are completely devalued and even punished on the SAT. For example, a young Latina new to America eagerly contributes to all aspects of the SBOE team’s work. Mention the SAT, and her eyes well up with tears as she describes what it felt like to be labeled “unsatisfactory” for the first time in her academic career. She had been a high achieving student in Mexico before coming to the US.

Through critical conversations centering his own experience, another student says, the literal “prison” aspect of the school-to-prison pipeline is irrelevant. “We’re in a mental prison right now,” he says. “We’re being set up for failure, and we know it.”

180 minutes, that’s it, 180

minutes to take a test that will determine at last

My future, my need is gonna

blast.

I look at the time, and my

thoughts begin to die…

At the fact that I’m still

on question 5.

The students believe that the policy solution is diminishing the SAT’s impact on the school ratings system. They would prefer that the entire rating system were revised or ditched altogether, but they know that sometimes smaller steps are more achievable than big ones. Just how feasible any of it is and whether or not folks in power will listen is anyone’s guess.

Story, though, is a healing approach for the students, and the Southwest SBOE team is good at liberally applying it as a salve. The students know they are labeled by the color of their school rating, and that narrow evaluation is incomplete.

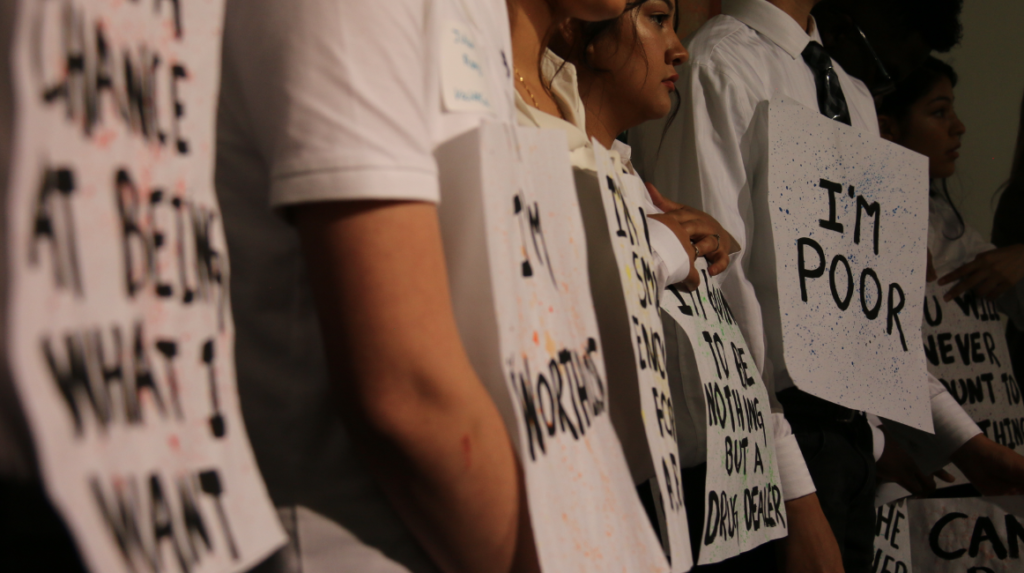

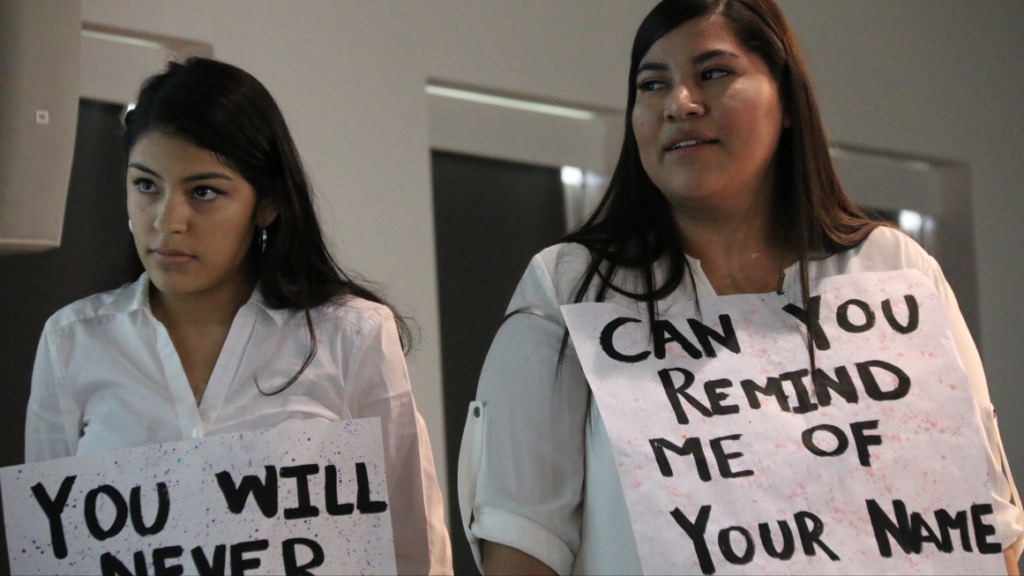

The SBOE’s experience in this kind of work has shown them the power of inquiry, expression and activism. The previous year, they used poignant personal anecdotes as the hook for their policy proposals. In 2018-19, they researched teacher bias. Their presentation began with each student wearing physical paper labels with vignettes written on each. For example, one student’s paper indicated that a teacher said the student would never amount to anything. A Black male’s paper said a teacher once told him his smile made her nervous. Another’s said simply, “I’m poor.” At the end, after putting forth a strong policy solution that recommended school officials implement better implicit bias training for teachers, the team ripped up the vignettes and declared they were more than their labels. Students from other high schools voted to award the Southwest team the top spot in the competition.

These examples and many more demonstrate how story can pull on heartstrings and call folks to action. And backing those stories up with research can strengthen the message and accelerate change. This year, the Southwest team has been busy surveying and interviewing students about their perceptions of and experience with the SAT. Their data was the basis for the poem featured in this piece. The students have worked through a process of critically analyzing official or archival data from media sources and the websites of school districts and the state department of education. They’ve also engaged with several power players and community members on both sides of the issue to more deeply understand the context of testing and school ratings.

That work is nothing, however, without the stories, which function as counter-narratives that challenge dominant discourse and humanize the students’ policy recommendations. Consider the stanzas above. Who does the average middle-class US citizen think of as a test-taker? What kinds of knowledge are being prioritized and marginalized in such tests? Who gets to be labeled proficient vs. unsatisfactory? The students’ stories lay bare the flawed logics and dangerous assumptions baked into assessment and accountability efforts.

These students’ life experiences shared in the form of story take us below surface-level perceptions. They expose politics, systems, ideologies and impact. They place the power to write one’s story exactly where it belongs: in the hands of the person experiencing it.

I am tired and hungry, my mind

sees breakfast instead,

I’m so uncertain,

I don’t want to take this test.

Resources:

For more information on centering youth experience through story, check out:

- Transformative Student Voice curriculum (especially 3C: Counternarrative)

- The author of this piece sharing a Map to Write narrative strategy.

- The National Writing Project’s Civically Engaged Writing Analysis Continuum

- Poet Warriors Project

- ProPublica’s Miseducation project, which includes demographic and opportunity gap information.

Dane Stickney is a senior instructor and doctoral student at the University of Colorado-Denver, where he focuses on sociopolitical development, critical pedagogy, teacher licensure and community and family involvement in education. He is a field researcher, teacher trainer and curriculum designer through a research-practice-partnership grant between Rowan University, the University of Colorado-Boulder, CU-Denver, Denver Public Schools, and the Philadelphia Student Union. He worked as a newspaper reporter before teaching middle school writing and history. Reach him at dane.stickney@ucdenver.edu.