Originally posted on EdWeek’s Learning Deeply Blog on October 11, 2017.

Our current political climate and all it portends about our democracy has alerted many Americans to a striking fact: civic education needs a makeover. Currently, only 23 percent of high school seniors are proficient in civics, according to the National Assessment of Education Progress, and just one in five young citizens voted in the 2014 midterm election. Further, my colleagues and I at CIRCLE have found that less than one-third of American youth believe that living in a democracy is essential. Clearly, we need to do more to ensure that young people are sufficiently prepared and motivated to participate in civic and political life.

One reason for these disturbing trends may be that opportunities for civic learning vary tremendously depending on students’ social class and where they attend school. Young people with a college education are three to four times more likely to engage in civic life through community leadership, volunteering, and political engagement than those without a college degree. This participation gap was evident in the 2014 midterm election when 32 percent of young people with a college degree voted, while just 8 percent of youth without a high school credential cast a ballot.

As a director of a think tank that focuses on youth civic learning and engagement, I’ve seen abundant evidence that a lack of civic engagement, coupled with gaps in opportunities to learn civic skills and develop democratic dispositions, are grave problems, not just for individuals, but for our society as well. I have long worked on addressing both the engagement and opportunity gaps by helping stakeholders to see where these gaps exist, and then by studying curricula and programs that help to promote civic readiness among students who are furthest from opportunity. As a Distinguished Fellow with the Student-Centered Learning Research Collaborative, I have developed a framework to address this challenge. And it’s a simple one: Keep It Student-Centered, Stupid (K-I-S-S)!

Preparation for civic life, especially for those who are historically marginalized, will be most effective when it begins with building a sense of agency and purpose.

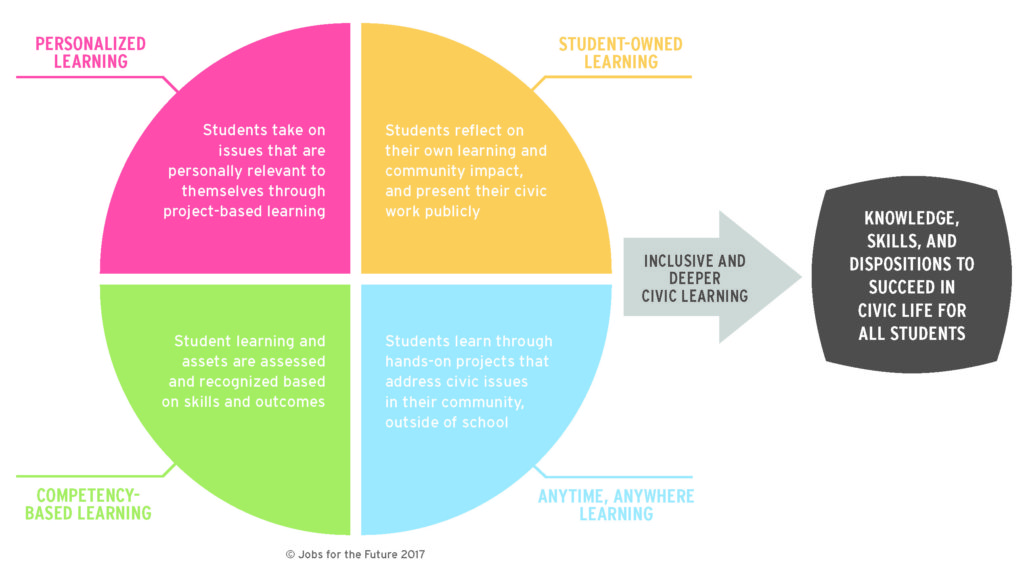

The Students at the Center framework, developed by Jobs for the Future in 2013, is a useful tool to conceptualize a new model of civic education that foregrounds equity of opportunity and democratic participation. The traditional model of civics education typically places acquisition of content knowledge at the center. This move to prioritize content is based on an assumption that knowledge will build motivation and skills, which will then lead to success in civic life. More recent studies that take a closer look at what motivates and engages underserved youth suggest that this model doesn’t hold up, particularly when youth do not see their place in our democracy. That is, our civics and government courses too often tell students about American democratic society and the role of citizens in sustaining and strengthening it, without letting students of all backgrounds practice the skills required to actually live in a democracy. We know from research that not all youth believe the American democratic principles apply to them and not everyone has equal opportunities to experience democratic practices at home (such as active healthy debates about political issues). Consequently, preparation for civic life, especially for those who are historically marginalized, will be most effective when it begins with building a sense of agency and purpose, not when it relies on rote facts that have no relevance to students.

The Students at the Center framework, above, supports development of inclusive civic learning environments and provides insights as to how students can develop their deeper learning skills. The framework helps us build a more student-centered set of approaches to civics. Knowledge of our systems and rules can help some–but not most–students succeed in civic life. The rest need to experience what it is like to have a voice, to be recognized for their assets and skills, to integrate the perspectives of others, and perhaps most importantly, to be able to take informed action on an issue that matters to them. Having authentic agency and taking real-world civic action are essential in preparing students to succeed in civic life, especially in the era of global shifts in power, political polarization, and growing distrust toward government and institutions.

Student-centered civics begins with the observation that an active citizenry results from active engagement with democratic principles. Putting students at the center of those activities will ensure that they have what they need to keep our democracy healthy, responsive, and just in the decades to come.

Look for more posts in the coming months that unpack this new framework. In the meantime, check out Rethinking Readiness for further reading on the importance of civic education for all students.

Kei Kawashima-Ginsberg is a Students at the Center Distinguished Fellow and the Director of CIRCLE, the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement, part of Tisch College of Civic Life at Tufts University.