When I was starting out as a youth worker in San Francisco’s Mission District in the 1990s, I saw powerful examples of multiracial youth organizing: young people, often working with young adults, investigate damaging or unjust education policies, develop promising solutions, and press for policy change in their schools and communities. These groups are not just spaces for policy change. They also offer transformative contexts for marginalized youth to learn and claim power. Organizing groups, such as Philly Student Union, offer learning environments where youth come together to share stories, identify injustices, and organize campaigns to influence policies that affect their lives.

Less common are examples where our public schools nurture robust civic learning of this kind, where students have a voice in decision-making and explore topics relevant to their lives. Too often, a laser focus on academic testing overshadows the civic mission of public schools and, more broadly, school policies and practices can undermine young people’s sense of belonging and dignity. Hopes for a more equal and vibrant democracy depend on public schools. Young people and their families fight for high quality neighborhood schools because public schools and the teachers who staff them are guardians of the democratic promise of America.

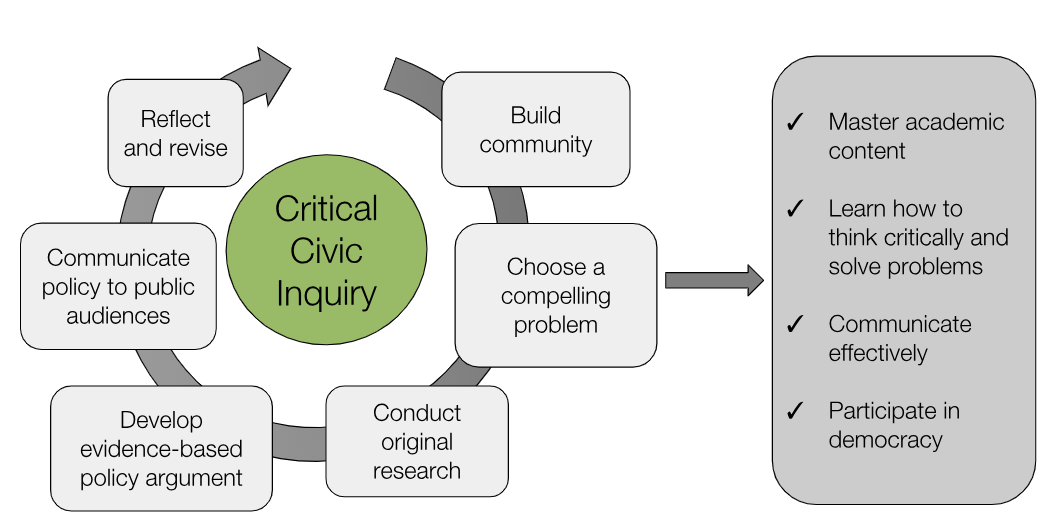

Why not learn, then, from community-based youth organizing spaces to inform the design of rich democracy education inside of public schools? This is precisely what we did when developing Critical Civic Inquiry (CCI), a social justice approach to student learning, teacher development, and structural education change. CCI aims to leverage the insights and practices of teachers and community educators to strengthen opportunities for transformative student voice in public schools.

Critical Civic Inquiry cycle of learning and student outcomes

Source: Critical Civic Inquiry Research Group

The Origins of Critical Civic Inquiry

In 2008 I received a phone call from Shelley Zion, a sociologist of education from the University of Colorado Denver, whose dissertation looking at student voice had identified a troubling phenomenon. In her focus groups with students from around Denver, Colorado, Shelley found that students in the poorest and most marginalized schools articulated an analysis of educational inequality but tended to report that there was nothing that they could do to address the situation. Their schools, although successful at cultivating a deeply held belief in meritocracy, had failed to cultivate a sense of civic empowerment. Shelley’s work echoed prior research on youth “resistance,” which identifies the varied ways that young people may resist the injuries of toxic schools but not necessarily channel their desires and fears into organized collective action. Shelley invited Carlos Hipolito-Delgado, who studies ethnic identity and school counseling, and me, because of my work on youth organizing and student voice, to develop a collaborative project. Carlos brought his prior research on issues of internalized racism and ethnic identity development in Chicana/o and Latina/o communities, as well as a critique of the limitations of typical school counseling practice and a vision for transformational school change. I brought prior research about the learning environments in multiracial youth organizing groups in the San Francisco Bay Area, as well as experiences facilitating Youth Participatory Action Research.

CCI aims to collaborate with teachers and administrators to co-design opportunities for students to critically assess their school experiences and participate with adults in finding solutions. We start by developing a community of learners with teachers, who in turn facilitate a cycle of participatory action research with their students: students reflect on their school experiences, identify a problem, study it through systematic research, and then develop an action plan to raise awareness or change a policy. This focus is consistent with recent calls for an “action civics” that enables students to practice civic participation through authentic projects.

One distinct aspect of CCI’s design is to integrate it into a range of academic classes during the school day, including literacy, science, math, and traditional civics. This coming year we are collaborating with Denver Public Schools’ Student Voice and Leadership program to develop a professional learning community for classroom teachers to practice CCI in their classrooms. We believe, drawing on core principles from the learning sciences, that students develop deep understanding of academic content by using academic tools and concepts to study and solve complex problems. These classes aim to deepen student engagement by embedding content in an action research project about an issue relevant to student lives, such as clean drinking water (science), college matriculation rates (math), or social relations among racial and ethnic groups at the school (literacy). By working on open-ended problems, without a preset solution path, students develop a deeper and more agile type of adaptive expertise.

How do you integrate CCI into your instruction? Through iterating on our ideas since 2008, our team has identified four core practices. Although initially designed for academic courses, these core practices also apply to out-of-school settings aiming to engage young people in leadership and social change. CCI curriculum is currently being developed and piloted and will be available as an open source resource in September 2019.

Critical Civic Inquiry in Schools: Key Practices and Definitions

- Sharing power with students: Educators make an effort to learn about young people’s lives and the kinds of knowledge they develop outside of school. Students experience some choice, within parameters set by the educator, related to curriculum and projects. Students practice how to make collaborative decisions. Sharing power is fundamentally a relational approach to teaching. This means that educators also share something of themselves: they locate themselves for their students and aim to be an ally for their students’ development.

- Exploring critical questions: Educators invite students to discuss topics related to race, ethnicity, power and privilege. For example, what would it look like to have a culturally sustaining curriculum? What are microaggressions? What are the historical roots of contemporary anti-immigrant rhetoric in the US? Critical conversations recognize that current oppressive conditions are not natural or inevitable. Such conversations open up the possibilities for what kinds of issues youth select to work on and are open to discussing in the classroom.

- Participatory research: The centerpiece of CCI is an action research project in which students study about an educational barrier at their school and then develop solutions to it. Students learn how to conduct and document interviews, administer surveys, and perform archival research. They analyze data to identify patterns and themes. This process emphasizes student-centered learning, including initiative and planning, teamwork and collaboration, reasoning about data, and communication.

- Structured presentations to the public: Students formulate an evidence-based policy argument that they share with external audiences, including guests from outside the school walls. This is both an opportunity for institutional change and leadership development for students.

Additional Resources

- www.studentsmakingpolicy.net

- Kirshner, B. (2015). Youth activism in an era of education inequality. New York: NYU Press.

- Find student action research (also called youth participatory action research) lessons at http://yparhub.berkeley.edu

References

Levinson, M. (2012). No citizen left behind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. doi:10.4159/harvard.9780674065291

Rubin, B. C. (2011). Making citizens: Transforming civic learning for diverse social studies classrooms (1st ed.). London, UK: Routledge.

Tuck, E., & Yang, K. W. (2014). Youth resistance research and theories of change. New York, NY: Routledge.